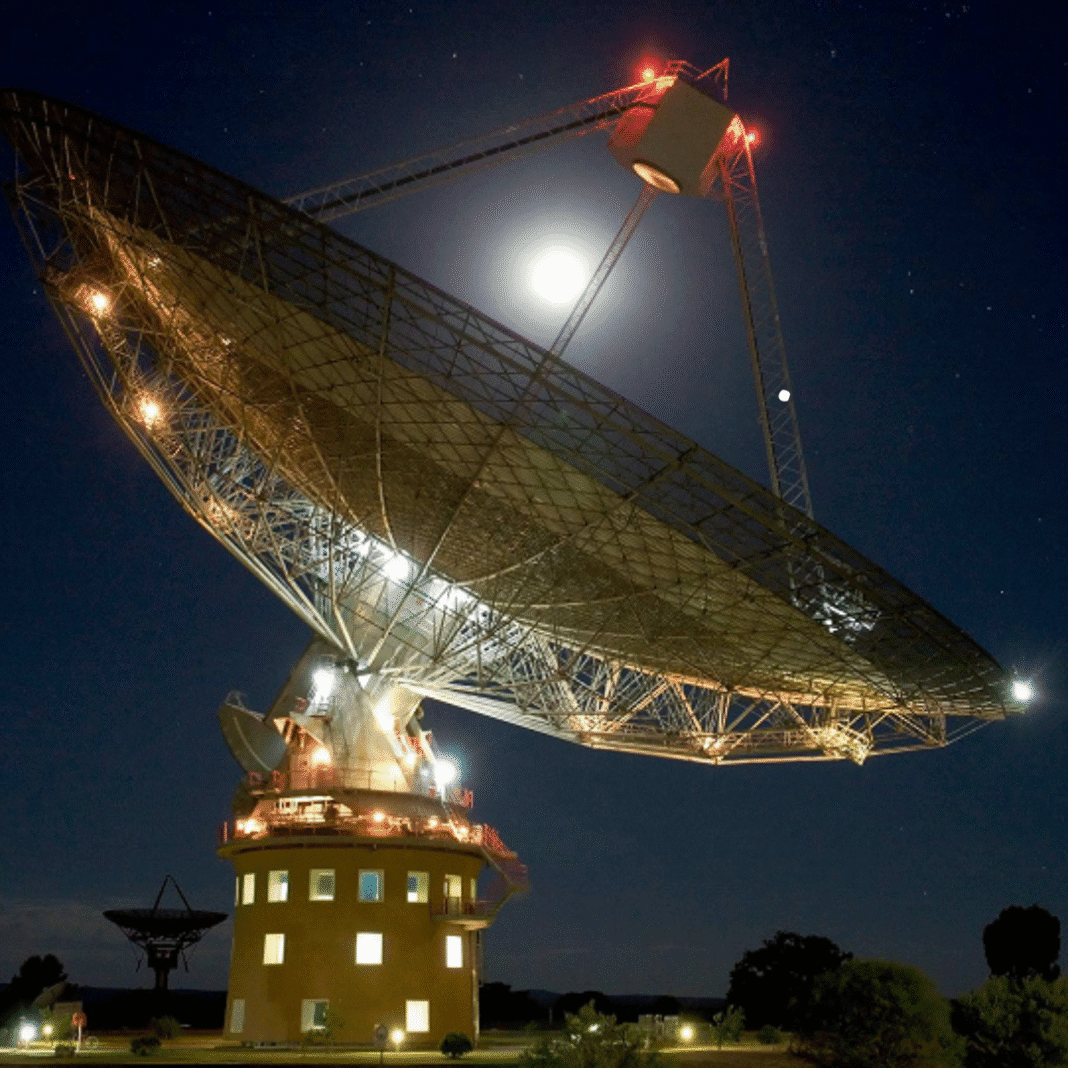

Every time you check the weather forecast, use a GPS app to navigate, or watch a live sports event from across the globe, you rely on satellites. These satellites, circling far above Earth, send data down to us using invisible waves of energy called the electromagnetic spectrum. This spectrum stretches from high-energy gamma rays to the low-energy radio waves. The radio frequency spectrum is the area that satellites use the most.

The radio frequency spectrum functions similarly to an enormous information highway. TV signals, cell phone calls, and satellite data are all carried by it. This highway is divided into smaller sections called bands. Satellites need these bands to send their information back to Earth. But there’s a problem—this highway isn’t endless. There’s only so much space, and more and more satellites are fighting for a spot.

With over 11,800 satellites already in orbit and tens of thousands more expected in the next few years, it’s getting crowded. If two satellites try to use the same band at the same time, they interfere with each other, and the signals can get mixed up or lost entirely. This makes it hard for people on the ground to receive clear and accurate data.

The Challenge of Fair Access and Regulation

The rules for using the radio frequency spectrum are set by an international group called the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). The ITU tries to make sure countries and companies use these bands in a fair and organized way. But there’s a catch: the rules favor countries with big space programs. Since the ITU uses a first-come, first-serve system, the countries that started using the radio spectrum first get to keep their bands. This means countries with fewer resources, especially in the developing world, are left out. They struggle to get the space they need for their own satellites.

10 Satellites, 9 Targets, 1 Mission—ISRO’s Role in India’s Stealth Strike After Kashmir Attack

The ITU’s system also has no real power to stop countries from breaking the rules. If a country decides to use a band that’s not meant for them, there’s no punishment. So, even though the ITU has rules, there’s no one to make sure everyone follows them. This creates a situation where powerful countries and big companies can take up more space, while smaller countries are pushed aside.

Some experts believe that every country should have the right to access the radio frequency spectrum, no matter how big or small their space program is. They argue that access to satellite data like internet services, navigation, and weather forecasts is a basic need, just like access to clean water and electricity. They suggest that all countries should agree on fair rules and stick to them so that everyone benefits.

New Tools and Ideas for Managing Satellite Spectrum

The fight for radio frequency spectrum is getting more complex. The more satellites that go up, the harder it becomes to manage the limited space. But new technologies might help solve this problem.

One idea is to use smarter technology to make better use of the bands we already have. Some experts are looking at millimeter-wave spectrum technology, which uses much smaller sections of the spectrum to handle more data. Another idea is dynamic spectrum sharing. This means different services, like mobile networks and satellites, can share the same band without getting in each other’s way. There’s also software-defined radio, a tool that allows radios to change frequencies on the fly. This helps them avoid busy bands and keep signals clear.

From Space with Malice: China’s Satellites Tipped the Balance in India-Pakistan War

Other researchers believe that game theory a kind of math used to predict how people or systems will behave can help. They suggest using formulas to figure out the best way to divide up the bands fairly, so everyone can get what they need.

Some believe that it might be best if governments step back a little and let industries figure it out themselves. They think a system where companies manage their own use of the spectrum, with only a few rules set by governments for public safety, could work better than the current system.

As the number of satellites grows, the need for fair and smart ways to share the radio frequency spectrum becomes more urgent. Without better solutions, the risk of interference and unfair access will only grow, making it harder for people around the world to benefit from the incredible services that satellites provide.